Experts Weigh in on New and Upcoming PCI Technologies

New Technologies: Boston Scientific’s Guidewire Footprint and the Future of Stenting

Why do we Continue to Innovate in the Stent Space?

Craig Thompson: With stent technology, Tim, from your perspective why is there need to innovate in the stent space? Given how good current durable polymer drug-eluting stents are, why move towards the SYNERGY product?

Tim Girton: That's a great question. It's a question we get all the time, actually. I think we've made some large leaps from POBA to BMS. Again, some large leaps from BMS to DES. I think today's SYNERGY makes another leap to minimizing stent thrombosis. If you look on aggregate at the results of today's DES-like SYNERGY, high degree of efficacy, incredibly low stent thrombosis rates, a high performing product overall.

I think in general the innovation's going to move in the space with SYNERGY and with other stents to looking at some of those niche applications where the results today aren't quite as optimal as they could be.

Craig Thompson: You know, even in work-horse type lesions, I think one of the concerns had been escalation of event rates that occur over time, so there's lack of flexibility from a physician's perspective with respect to delaying platelet therapy for patients and unexpectedly have challenges there.

Part of the supposition from Tim and his team within the company, and there's been good clinical data to support this, is that ongoing exposure of a durable polymer in a vessel, day after day, month after month, year after year, particularly after you've lost the protective effect of the drug, Everolimus in the case of SYNERGY, and Promus Premier is disadvantageous, maybe driving along these late events, stent thrombosis, neoatherosclerosis. What's your take? Is there a role to improve above and beyond the second generation durable polymer drug-eluting stents, permanent polymer drug-eluting stents, with a third generation absorbable polymer DES like SYNERGY that's really driven towards vascular healing?

Colm Hanratty: The late complications of the durable polymer like you have mentioned, there will be a penalty, a small penalty, but for the patient that has that penalty that can be catastrophic. I think we're striving to improve on very, very, very good outcomes and it's going to be very hard to show improved outcomes, but nonetheless we should continue to strive towards that to shorten dual antiplatelet therapy for people, and to have longer term, better outcomes with regards to stent.

What Engineering Features of SYNERGY Improve Clinical Outcomes?

Craig Thompson: In terms of specification stent ... SYNERGY, just to familiarize everybody that's watching, is a very thin strutted platinum chromium stent, has an abluminal, meaning only on the outside, coating of a wafer-thin polymer that carries the drug.

The polymer and drug are absorbed over several months together after they limit neointimal response. Therefore, you don't have this ongoing hazard of polymer exposure. In terms of this particular technology, either compared to current and prior technologies or looking forward, what are the aspects of a stent platform that you as a clinician feel are important, the big levers to make outcomes better, flexibility for physicians?

Colm Hanratty: I think as the population we're dealing with becomes older with more comorbidity, prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy will have a consequence. I think that the acute performance of the SYNERGY stent, its visibility, its ability to over-expand the full range of anatomical situations we can deal with effectively is very, very important for us.

Craig Thompson: Tim, with that in mind, what are the technical levers that you pulled, you and your team, I should say, pulled with SYNERGY in order to try to optimize performance over our previous generation products?

Tim Girton: The leverage we pulled, Craig, were really around a polymer that degrades as rapidly as possible while maintaining the drug release that we know to be effective with Everolimus. With SYNERGY, we have a drug and polymer that degrade within roughly three months, polymer gone in three months, drug gone in three months.

The other things we put into SYNERGY, though, are these pleasure factors for an acute performance perspective, things like good overexpansion, great radial strength, good radiopacity, and then some brand new technology in the laser cut hypotube that allow much improved deliverability over what else is out there. We addressed both the acute as well as the medium to longer term clinical aspects with SYNERGY.

SYNERGY Use in Everyday Complex Patients

Craig Thompson: Colm, you and your team in Belfast has actually evaluated SYNERGY and the most complex patients, so basically patients that are levered for not only the acute performance issues, which Tim and team were designing around, but also potential adverse outcomes associated with adverse healing phenomenon, at least on the lesion specific basis. Can you comment on what your experience has been thus far in this highly complex population?

Colm Hanratty: Sure. To set the scene, the stent price in the United Kingdom had fallen to, it was about 300 pounds per stent. Whenever SYNERGY came along, they came in at a slight 20% premium above second generation drug eluding stent. We're mindful of cost in the National Health Service, as are most healthcare providers, so we had to make an argument, a justification, to our managers that this would be used in clinically indicated, which ultimately became patient population.

You had to be on Warfarin or a NOAC; extreme old age, a frailty score which is usually an eyeball test; upcoming known cardiac surgery where 12 months of DAPT would be maybe not helpful in the outcome of the patient; anemia, and risk of bleeding. To get a SYNERGY stent, you had to tick one of those boxes. Then, Simon Walsh and myself, 185 consecutive patients over a three-year period, we looked at the outcomes and what we found was that even though it was a complex cohort of patients, each stent left them over 70 millimeters. The stent thrombosis rate at six months, and in fact out to 330 patient years, was 0%.

Craig Thompson: That's phenomenal. Tim, does this surprise you?

Tim Girton: It doesn't surprise me. It's what we hoped to see, but it's very gratifying to see, again. You never know on the bench top exactly how much clinical benefit you're going to have until you actually get it in the hands of the clinicians. It's very gratifying, again, to see the results that come out from the clinical studies.

Fully Absorbable Platforms – Where are we going?

Craig Thompson: There's fully absorbable platforms in various geographies of the world that are commercially available. There are some that are in development. We have our own internal program, Tim, which you lead, that we call Renuvia. Colm, what is your view on fully absorbables in terms of need, potential, limitations, upsides, downsides of that particular technology?

Colm Hanratty: I think it's going to be very hard to show improvement in terms of short term outcomes over contemporary third generation drug-eluting stents. I think that's going to be a real challenge.

There does appear to be an appetite for the fully absorbable stent, but in terms of achieving the acute performance we've come to expect, it's going to be very hard, I think, to achieve that.

Craig Thompson: Tim, I think there are two issues that Colm brought up. One is acute performance and how good can we get with that from a materials perspective with at least currently available polymers to develop a fully absorbable stent, or metals, for that matter. Then the second issue is long term outcomes and the perspective of being able to engineer something that would be appropriately biocompatible over a long period of time. Thoughts from an engineering perspective?

Tim Girton: Yeah, it's an incredibly challenging problem. As you know, we've been working on this internally for half a decade, really. My thoughts on acute performance is you're always going to give something up in acute performance with going with a plastic stent or even a metal biodegradable, for that matter, versus a good metallic stent.

I think there'll always be limitations with a fully biodegradable stent relative to a metal stent in the acute performance. I think the same thing is true for the long term performance as well, because what is going to happen, at least for the first several years, is as these stents break down they tend to fracture. As they fracture, you induce potentially more risk for things like stent thrombosis that I actually think we're seeing in some of the long term data that's been published more recently. There's a certain price to pay up front, and even medium term, in order to have the benefits long term that in my mind still need to be proven.

If I can just expand a little bit on our approach, we're looking for a true second generation device. We think we need to make a pretty big leap forward in terms of technology in order to not pay such a steep price in the first several years to have the benefits that hopefully will be there long term with a fully biodegradable stent. But what I will say is that our target also is to make sure that these stents are likely going to be used in more niche applications. I think proximal lesions, less calcific lesions, larger vessels, younger patients, and maybe even patients that need to tolerate DAPT for years while the stent is breaking down are probably the ideal subset of patients for a technology like this, but the technology still needs to take that jump to be less onerous from a clinical endpoint for the first couple years.

Guidewires – Demystifying Wire Technology

Craig Thompson: Tim, I'm wondering if you can speak to what you and the team were seeing in the field in terms of considerations of what we need to do in order to have a very broad based, comprehensive guide wireline and what the targets were there.

Tim Girton: Yeah. Quite simply, we were looking for a technology that really gets us beyond today's generation's wires. Actually, today's wires are reasonably good so there are a number of manufacturers that make good wires. We were looking for a partner, and we found one in Japan that has unique technology that makes for a better wire performance, sort of across the board, both in the work horse segment of wires as well as the more challenging complex case wire portfolio. We partnered with a company in Japan that has that specific process technology that they bring to bear on these tools. We're hearing very good feedback from Sentai in terms of performance.

Craig Thompson: Very good. Are there any unmet needs in terms of wire lines them self, guide wire lines, or training to use these? Is this changing a paradigm?

Colm Hanratty: What we actually have to do is demystify the whole wire technology and make it less complex. Some companies have up to 80, 100 wires. I think for conditions, especially if you're a low volume operator and low volume center; it's very hard to retain that information. That's why breaking wires into simple categories... What is it designed to do? Is it designed to go through a micro channel? Is it designed to go cross a collateral channel? Is it designed for work horse purposes? Is it designed to penetrate through a proximal cap? Is it designed for externalization? Then I think you're into physician education.

There are plenty of little models available now which demonstrate the torque control of these wires. I think whenever people see it and get their hands on the wire, comparing separate wires, that is very instructive in terms of what the wire's designed for and then how it would fit into their day-to-day work.

Craig Thompson: Buckets. Application buckets.

Tim Girton: Simple buckets.

Craig Thompson: Simple buckets. We can do this. Well, Colm, Tim, thank you very much for your time today and insights on next generation technologies.

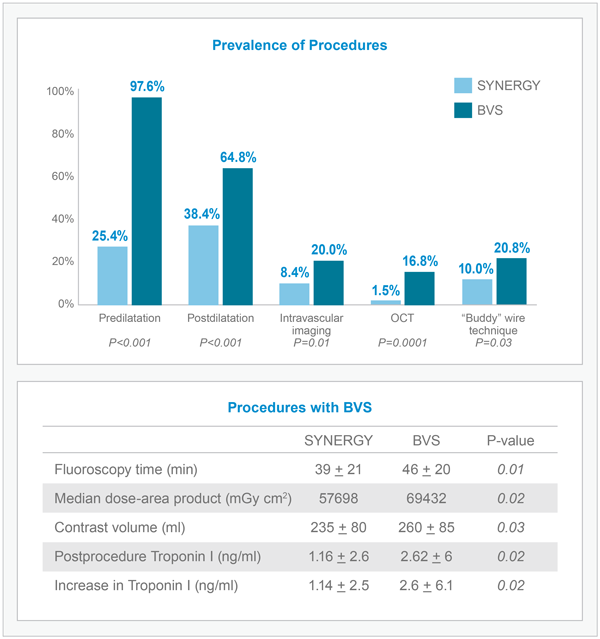

SYNERGY Procedures Utilize Fewer Clinical Resources Compared to BVS